It has been only a few years since I first became aware of the Finnish artist Helene Schjerfbeck. I wish this had happened sooner, but I’m glad it happened at all.

I find her work fascinating for several reasons, perhaps most of all because of how it developed in a career lasting more than sixty years. Over such a long period, change is of course to be expected, but this is nevertheless a remarkable example. In terms of style, technique and imagination, it’s almost unbelievable that a Schjerfbeck painting of the 1940s was created by the same person as one produced in the 1880s.

She never fully recovered from a fall at the age of four, which damaged her hip beyond repair. Her movement was inevitably restricted, but that might in turn have caused her to spend more time sitting at the easel in her youth, and therefore to learn her craft more quickly, than she might otherwise have done.

She was still in her teens when she painted Wounded Warrior in the Snow (1880). The style is not one I’m normally drawn to, but the tension created by the strange angle of the partly fallen tree, and the way the soldier’s colourful uniform stands out so strongly from the muted background, make the picture compelling.

There is also the question of whether the distant figures on the right are walking towards the soldier, ready to help, or away from him, leaving him to die. If they are approaching, Wounded Warrior is straightforwardly romantic and uplifting. If they are abandoning their comrade, it is both brutal and poignant. I suspect the latter, not least because brutal poignancy was, as we’ll see, something of a Schjerfbeck speciality.

That said, she did not employ it all the time. In 1882, the year she turned twenty, Schjerfbeck painted one of her most famous works. Dancing Shoes is in the Realist style, which she would have become very familiar with while studying in France. Realism, in this context, doesn’t mean quite what it seems to mean today; no one who looks at Dancing Shoes could be fooled into believing that it’s a photograph rather than a painting.

Described in very basic terms, the Realism movement was a rejection of supernatural elements in art. Realist paintings depict people who could have existed and events which could have happened. In this case, the girl definitely did exist. She was no invention, but Schjerfbeck’s young cousin Esther Lupander, nicknamed ‘grasshopper’ because of her exceptionally long legs. (One early viewer said they couldn’t believe any real child had legs like that, to which Schjerfbeck replied, “In that case, you haven’t seen Esther.”)

There is no brutal poignancy here. In Dancing Shoes, Schjerfbeck conveyed charm, as she did equally brilliantly in the beautiful Mother and Child (1886) and The Convalescent (1888). Understandably, these and other works of a similar kind are loved and celebrated, in a way that what was to follow perhaps never will be.

Schjerfbeck’s art is always figurative. Her exact contemporary, the Swede Hilma af Klint, is now regarded as possibly the first abstract artist in the modern sense, having adopted this style as early as 1906. (Wassily Kandinsky’s first known abstract composition, for example, was painted four years later.) Schjerfbeck was probably aware of her, but not of those paintings, since af Klint was well known for her more conventional art and suppressed the abstract work, not wanting it to be seen until after her death.

It’s impossible to say how Schjerfbeck would have reacted if she had been aware of what af Klint was doing in secret. She might have chosen not to take inspiration from it, but her own art certainly became, if not abstract, at least abstracted.

Among many other examples, this can be seen in The Family Heirloom (1916). It is unquestionably figurative, but if you somehow saw only a small part of it you might easily believe that it was an abstract work. This is, beyond all doubt, an image of two women, but while the younger Schjerbeck would have portrayed them in great detail, here she does so far more simply, but no less effectively, using large patches of colour.

Like the much earlier Wounded Warrior, The Family Heirloom contains a mystery. There is no obvious sign of what the heirloom in question might be. The fierce red splashes, the bowed heads and the closed eyes suggest that it is not a cherished object passed down through the generations, but an inherited and possibly fatal disease – a chilling echo, if you like, of the figures walking away from the soldier portrayed thirty-six years before.

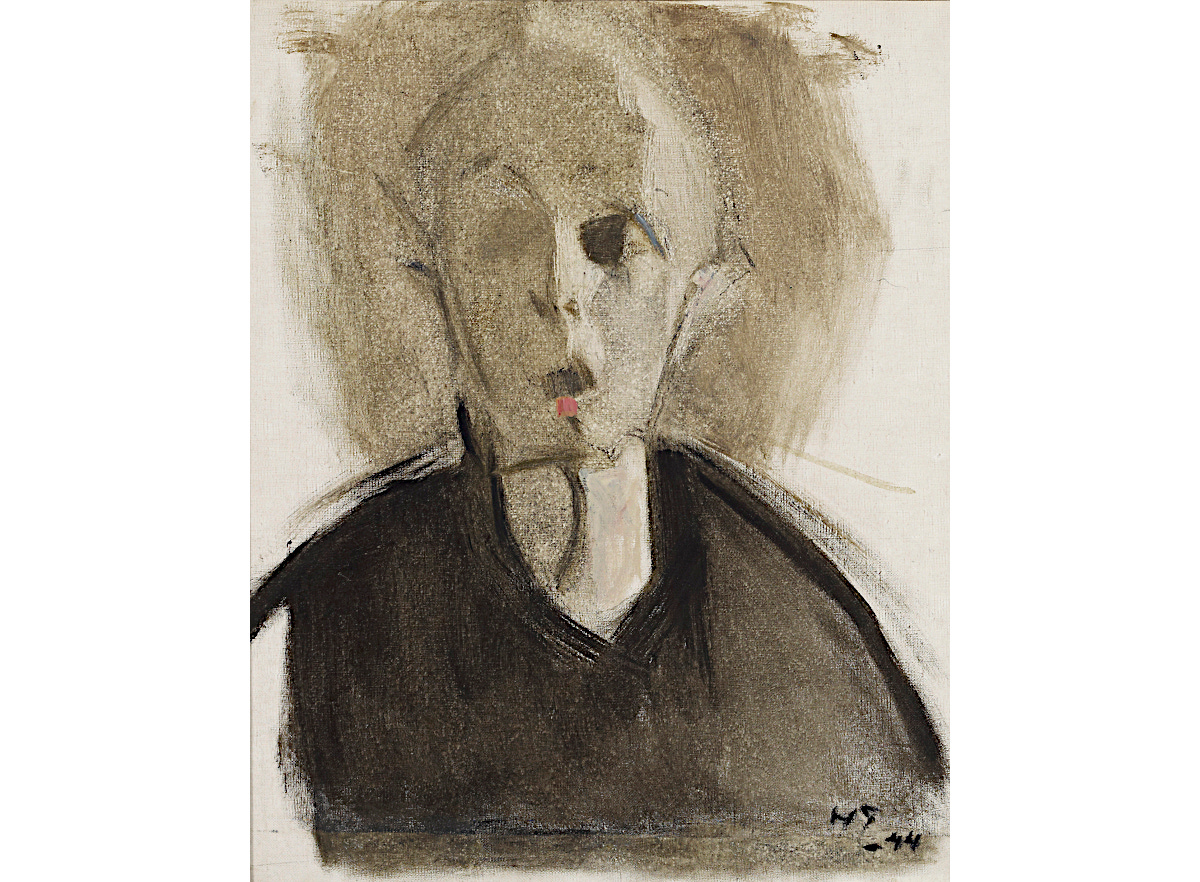

In the 1940s, Schjerfbeck herself became incurably ill, but she continued to paint. Her late self-portraits are, for me, the most extraordinary things she ever created, though I can see how others might not like them.

Artists in general – writers and musicians as well as painters – often portray themselves in their work. In many cases, such as those of L.S. Lowry or Edvard Munch, the results can be very disturbing. Pablo Picasso’s final work, painted less than a year before he died, is a self-portrait, and a terrifying one. It’s as if he was screaming, “No! Not yet! I have more to do!”

Schjerfbeck’s Self-Portrait With Red Spot (1944) is an even more horrific image, clearly painted by someone who knew her body would soon fail her, but I don’t hear Picasso’s scream. For whatever reason – the Finnish temperament is of course very different from the Swedish, but maybe it’s also because women can cope with these things better than men – I have the strong impression that Schjerfbeck is saying, as my mother more or less did when she was diagnosed with dementia, “Well, this is the way things are now. This is what happens. There is nothing to do but accept it.”

That might not be true. Artists can, and do, conceal as well as reveal. But I hope this is how she felt as the end drew near.

Helene Schjerfbeck, photographed in 1880 by Daniel Nyblin (1856-1923).

Top image: detail of Mother and Child.

All images public domain.

Recent posts

The Second Queen of Hirta chapter 13: Silly fellow

We Need To Talk, Mrs Kafka

The curious state of being British